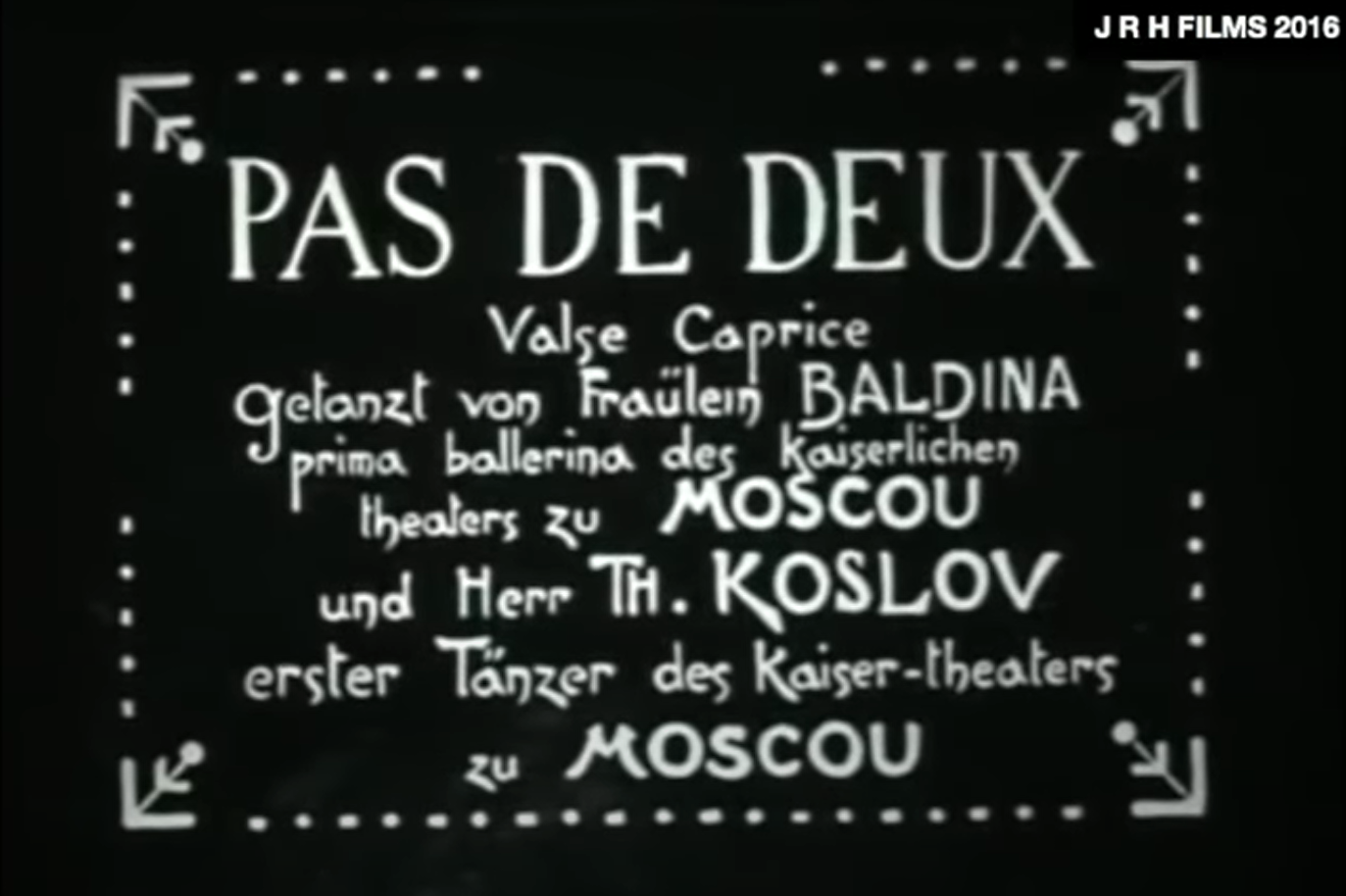

The following clip is courtesy of a YouTube combination—the invaluable John Hall YouTube channel first uploaded this film in a silent version; the channel passionballet.topf.ru added a musical score. The latter is the clip shown below (Hall’s original can be seen on his channel here).

As noted in the opening title card, the above is a 1909 film of Alexandra Baldina and her husband Theodore Koslov dancing a short pas de deux, “Valse Caprice,” choreographed by the legendary Nikolai Legat. The two dancers here are young and attractive, and as Hall indicates in his own video, Baldina has minor legendary status; she appeared in the 1909 Ballets Russes premiere in Paris of Les Sylphides, sharing the stage with Karsavina, Pavlova, and Nijinsky. One can only envy those who were there to see it.

Les Sylphides may not be off the mark for “Valse Caprice.” Baldina and Koslov wear costumes similar to those in the former work, such as Baldina’s couronne of flowers, filmy bell skirt, and off-the-shoulder top, and Koslov’s white tights, black doublet, and ghastly Little Lord Fauntleroy wig (which he removes for his variation). Was this PDD intended as a comment on Sylphides? A continuation? Or was it that these were the costumes on hand for the filming? I suspect the latter, as the piece lacks the haunted moonlight of Fokine’s great work. It’s basically a generic flirtatious-couple encounter—of two young people on the verge of falling in love, but still in the entranced delight of discovery. Any costumes from the bin would have served the purpose.

But why watch an old dance film like “Valse Caprice” today? It’s charming, though perhaps not remarkable by today’s choreographic or technical levels. Audiences watching it now (circa 2024), with no knowledge of the Ballets Russes or of turn-of-the-20th-century ballet, would probably not be impressed. But that’s missing the point. The film is a captured moment in time, like a mastodon caught in ice—an ungainly image, but you get what I mean. What’s remarkable is that it exists; it’s a record, saved on celluloid, of how dancers from another era performed, of what the technique was like, of what the performance aesthetic was like. It’s Time itself, arrested for four continuous minutes. If these dancers of 1909 could have seen, say, Fanny Bias, who danced 100 years before them (ca.1809), the effect might have been the same—not only is this the past preserved, this is past motion preserved. Even lacking sound or color or snazzy effects, it’s still Dance, the ephemeral art, here ambered for our eyes. How fortunate, and how rare, to have this tiny slice to view well over 100 years later. A great find, Hall calls it. It is, indeed. Past generations might even envy us.

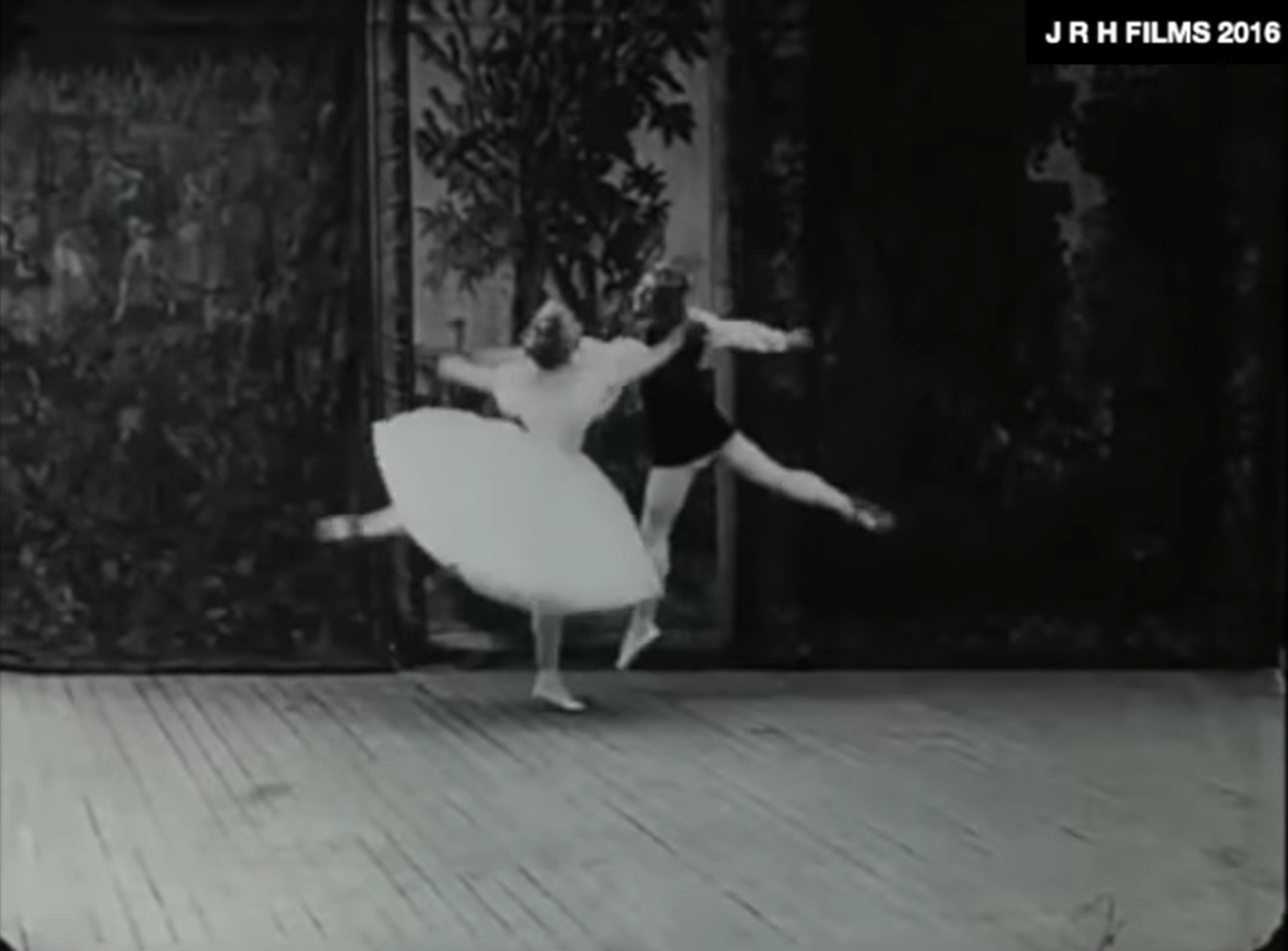

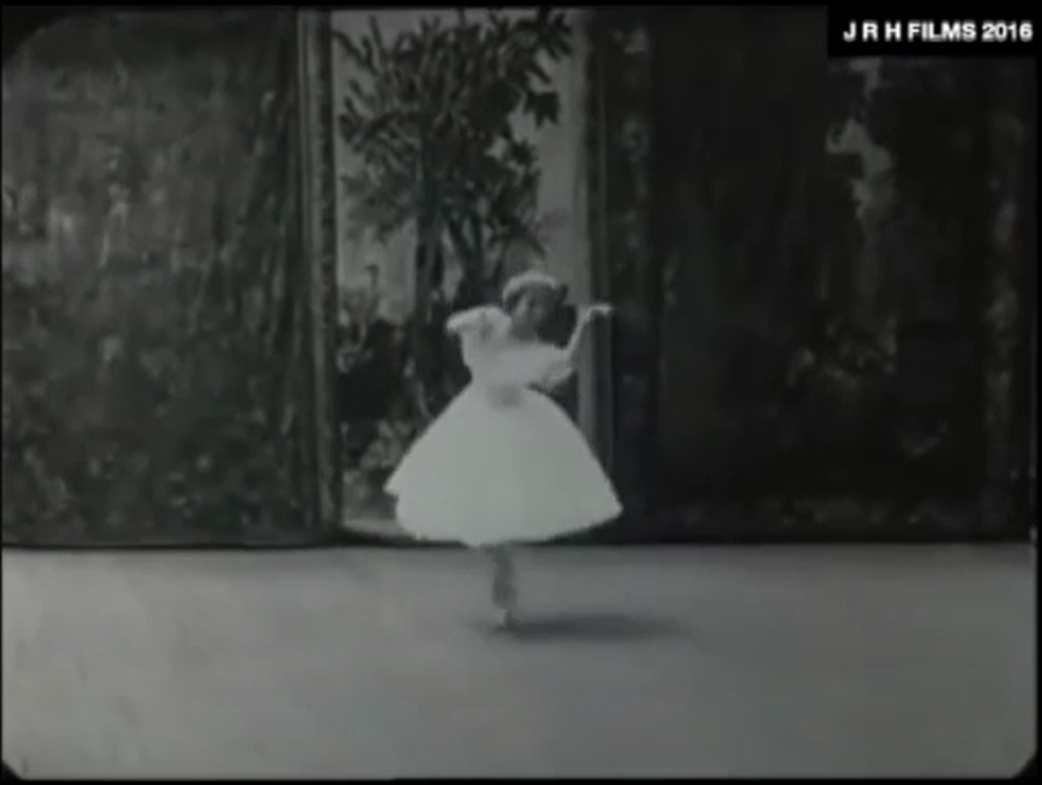

And the PDD is charming. Its construction is graceful, its flow sustains our interest, and its choreography expertly showcases its dancers. The dance starts with the ballerina entering from behind a curtain, preserving the stage effect, yet, because the space is so small, also preserving a sense of intimacy. She runs onto the stage, as if looking for someone, as she smiles in a girl’s secret, smiling way, innocent in thoughts of love. After walking in slow, deliberate steps, she then (reminiscent, perhaps, of Giselle) decides to dance, springing up in pas de chat, the movement so light and natural, she seems to float without effort, as if lifted by the air itself.

Then the man enters to court her, she inviting, then dodging his advances, he persisting in gentle pursuit. She moves rapidly in terre à terre steps, he bounds after her in rapid brisé combinations, leaping up to beat knees and feet together. She swiftly bourrées from him, her hands held aloft as if in mock balance; he then captures and lifts her, with feather-light ease. Near the end of their pas, she faces him (her back to the camera), he grasping her hand as she performs a slow développé devant. As she falls backwards, he catches her, an arm cradling her as he tilts her until her head is lower than her feet. They perform this move, which is repeated, without seeming to think about it—she smiling, confident, happy, he holding her securely, without strain, as if she were no more than the breeze in his arms. After exiting behind the curtain, they reappear to take their bows.

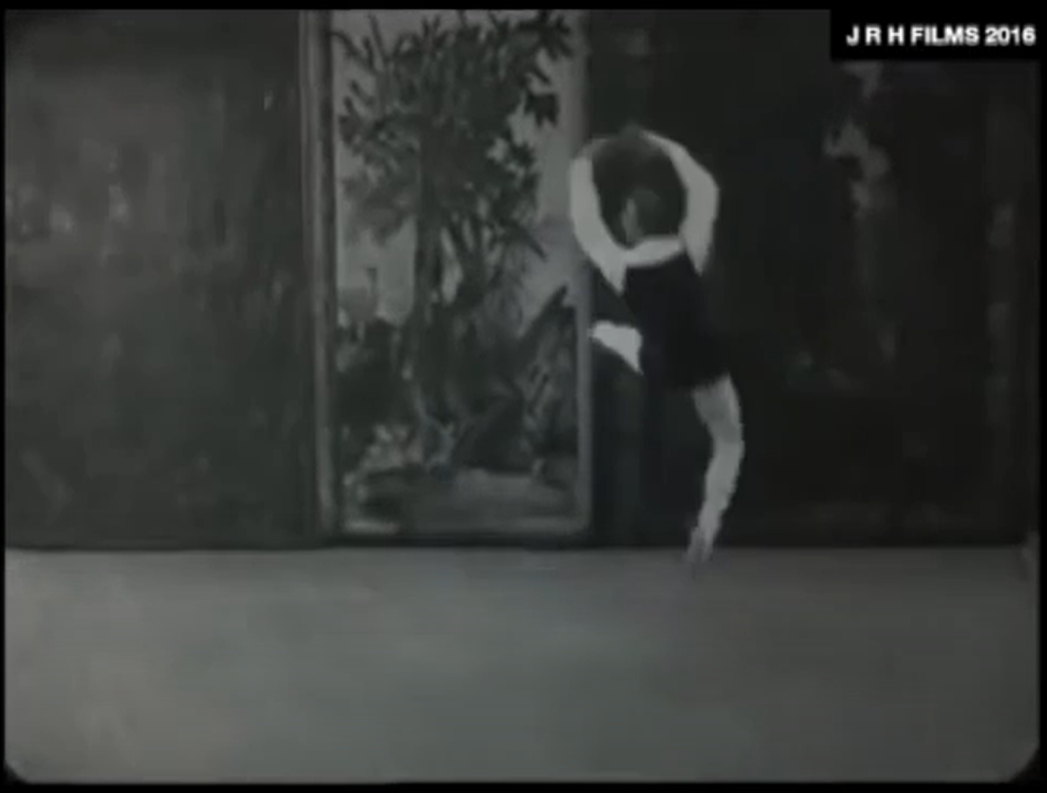

Koslov returns for his variation (sans that awful wig), posing in croisé devant, moving into small brisé beats, then leaping in barrel turns, before finishing with tours à la seconde that, in a melting movement of his working leg, become spins. In contrast, Baldina’s variation is quick and darting, with hops in arabesque and swift runs on pointe as she waves her hands (almost as if she’s playing a piano); her solo ends with her exuberantly raising her arms and gazing at the sky. Legat perhaps choreographed each solo to play to his dancers’ strengths, Koslov’s in ballon and rapid beats, Baldina’s in terre à terre skims, to then pose, breathlessly, in the lightest of arabesques, hovering sylph-like in the air.

Though considered virtuosos in their day, neither dancer has the flat turnout or overextended limbs of today’s dancers nor do they display, also by today’s standards, extraordinary technique. Yet the two have a lightness, a buoyancy, that is extraordinary. No strain or effort shows; he lifts her as if she were a dragonfly, she arches like a swan while perched in the air. And Baldina creates some wonderful, poetic moments, as when (at the .22 mark), she pauses, stretches her right arm, then slowly twists her upper body, leading with her left shoulder, to face the back, before continuing: The pause, the stretch, the twist to turn—she impels the movement, you sense how the pause stresses the twist, in which she luxuriates, enjoying the motion for itself. It’s a small but striking gesture, you’re vividly aware of how her torso rotates in space, how the gesture lingers, and how sharply she defines her movement. Note also (at the 1.49 mark) her pose upstage, one foot stretching in tendu, as she gently spreads her arms to greet her swain; there’s such amplitude in her gesture, it’s a motion not just of arms but of the entire upper body—a phrasing of spirit and feeling, opening herself to her partner and to the world. It’s dance performed as inner truth—an expression of deeper feeling at the moment it happens.

There’s a joy and simplicity in Baldina and Koslov’s performance, a genuine delight in their dancing. They obviously love what they’re doing, to which they bring such feeling; it looks not like a practiced art form but as their natural way of moving. That may be the secret to why their dancing is so delightful. They let the art show but not the artifice. Their bodies in motion appear not as something assumed and worked on ceaselessly, but as part of who and what they essentially are. Dance is the air they breathe. How can you not be enchanted?