I like to think of this scene as the ‘Holy-Cow-Is-That-CLARK-GABLE?’ Moment.

Yes, that is Clark Gable, attending a performance of what is said to be the Bolshoi Ballet in Swan Lake, from his 1953 MGM film Never Let Me Go. The film’s a tepid Hollywood Cold-War thriller, taking place in late-1940s Soviet-era Russia, with Gable as an American foreign correspondent in love with Gene Tierney, improbably cast as a young Russian ballet dancer. The plot has Gable’s USSR-assigned journalist kicked out of the country by nasty Soviet authorities after he marries true-love Tierney. Most of the film’s second half follows his scheme to sail a small craft from England to the Baltic Sea and rescue his wife from Tallinn…right when (and where) she’s dancing the lead in Swan Lake.

Yeah, the film’s as implausible as it sounds, though somewhat enjoyable; Gable looks nice in a military uniform, and Tierney looks nice in a tutu; and there are a couple of funny drinking contest scenes (if watching squiffy guys swilling enough vodka to float a boat to the Baltic is your thing). I’d recommend the film for diehard Gable and/or Tierney fans (it’s their only film together), or for 1940s-1950s Hollywood-Cold-War cinema completists (there are a gazillion such films). Otherwise…

You might find the film interesting for its dancing.

Per her autobiography, Tierney did train for her role (her teacher was Anton Dolin, also in the film as her dance partner), two hours a day for six weeks, “just to master enough technique to get on my toes and do the few steps…required of me.” Tierney was then thirty-two, “not an ideal age,” she notes, “to be taking up so strenuous an activity as ballet.” Her feet “were soon badly blistered and ached constantly”; Gable brought her a salve from Paris to ease the pain. In the film’s long shots of her character dancing, Tierney was doubled by “Natalie Leslie,” actually the Ballets Russes ballerina Nathalie Krassovska, in sections from Swan Lake. Although she has few scenes in the film (and those we see are interrupted by constant cutting), Krassovska does show how she was, as her New York Times obituary stated, “known for her lyricism.” Her dancing here is restrained, precise, and graceful, marking her, as Anatole Chujoy described in an October 1945 Dance News article, as “’a romantic dancer of fine style, excellent technique and great beauty.’”

Tierney herself, despite her crash-course training, doesn’t really dance in the film. She wafts her arms to make like a swan, and gazes yearningly at Dolin in closeups to simulate Odette’s passion. But she hasn’t a trained dancer’s body, she doesn’t stand or move like a dancer, and her gestures and poses lack dramatic weight. I don’t mean that as a criticism of Tierney. After all, she wasn’t a dancer; and what she does is adequate for the film’s purpose. Her casting was a matter of box office, not diegetic realism. And Tierney fans only casually interested in ballet probably wouldn’t have noticed her lack of dancing or cared if they did.

One question is why MGM didn’t cast an actual ballet dancer for the lead. The studio did have under contract a real ballet-trained performer, Cyd Charisse, who had already portrayed a dancer in the 1948 MGM film The Unfinished Dance (which I wrote about here), and who would later star as a (dancing) Soviet apparatchik in MGM’s Silk Stockings (a musical remake of Ninotchka), Russian accent included. Was it a case not only of box office appeal but of acting chops? (Although, per The Hollywood Reporter, Charisse had been under consideration for the lead.) However, Tierney was a known star with a following; and audiences of the time would no doubt have come to see the actress as Gene Tierney, Popular Movie Star. Even when portraying a (non-dancing) ballet dancer, her fans would have accepted Tierney as such.

That said, the movie’s three Swan Lake scenes (all from the second act), as filmed by director Delmar Daves, are not badly done. The first scene, introducing the two protagonists backstage at the Bolshoi, shows a sophisticated use of the camera, with a high crane shot dollying towards a seeking Gable (“I started looking for a swan…”), who then sees Tierney in the background. After a shot/counter-shot exchange of glances, the camera slowly dollies towards Tierney for her big intro closeup. Throughout, the camera work is fluid but unobtrusive, keeping the focus on the stars; it’s only after the main couple has been established that the scene cuts to a long shot of the four cygnets in their variation, one of whom we understand is Marya, Tierney’s character (though that’s not Tierney onscreen at this point) (clip courtesy of the TVVHS90s YouTube channel):

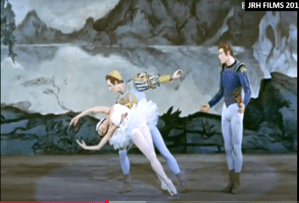

The second dance scene, after Gable has been forced to leave Russia, has Marya now promoted to the ballet’s lead. We see Tierney in closeup being lifted by Dolin, she facing the camera, her arms waving swan-like, her face in Odettean anguish. With the cut to a long shot of Odette and Siegfried separated by von Rothbart, Krassovska now takes Tierney’s place as the Swan Queen, her arms fluttering as she is impelled backwards towards von Rothbart, her (beautifully shaped) legs moving in a swift, tight bourree. Underscoring the scene is Marya’s voiceover, bemoaning (in a letter) the couple’s separation and expressing her hopes of a resolution (scroll to the 3:20 mark in the above video clip to see this second segment):

The third dance scene is the longest and most dramatic, with Gable now in Tallinn to rescue Tierney. Cinematically, it’s an elision: The segment begins with Tierney in closeup, waiting in the wings; as she raises her arms for her entrance, the camera pans screen right while Tierney exits offscreen; it continues panning, without a cut, until Krassovska (her back to the camera) bounds onstage with a pas de chat and pauses, in fourth position, her arms crossed in front (and it’s clearly Krassovska, there’s no mistaking her gorgeous legs). A reverse cut returns us to Tierney, the camera swiftly dollying to her face as she looks sideways at the audience, and sees (in a counter shot) Gable (wearing a stolen military uniform) watching her from the stalls. The scene continues with alternating closeups of Tierney and Gable, and long shots of Krassovska with Dolin, until it settles into the pas de deux proper, Krassovska finishing it by falling into Benno’s arms. The scene itself ends with Tierney fainting on stage as she takes her bows, setting up the film’s narrative climax (clip courtesy of the John Hall YouTube channel):

It was no minor undertaking for a movie studio, even a big one like MGM, to set up, rehearse, and film extended ballet scenes, including a corps de ballet. Perhaps box office appeal was behind this choice of film; the popularity of The Red Shoes had made American audiences ballet-conscious. Or maybe it was due to MGM having already produced another Cold-War-With-Ballet thriller, The Red Danube, in 1949; so, hey, why not do it again? (The film, unfortunately, was not a hit.)

As for Swan Lake as the movie’s ballet (rather than, say, a dance created specifically for the film), its choice is obvious. Though the ballet scenes are short, they make the point: Gable and Tierney’s characters have been separated in the same cruel way that Siegfried and Odette are. Swan Lake functions as Symbol here, underlying the narrative as dramatic device and metaphor. Another ballet would not have had such emblematic resonance. And by the 1950s Swan Lake was probably as well-known to American audiences, even movie-going ones, as The Red Shoes, its second act having been performed frequently by the various Ballets Russes companies that had barnstormed the country from the 1930s through the 1950s (Krassovska also danced for these companies).

And that brings me to the staging of Swan Lake‘s second act in the film. And as to how it was staged on stages circa 1952-1953.

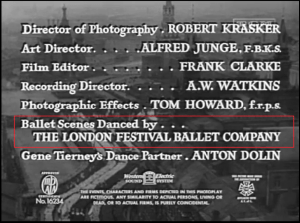

In terms of technique, style, even choreographic choices, the so-named ‘Bolshoi Ballet’ presenting Swan Lake to 1953 movie audiences is…not the Bolshoi. Although the film’s ballet company is labelled the Bolshoi, the actual dance company was the then-London Festival Ballet (the movie was filmed in England, hence a British company being used). Now known as the English National Ballet, it began life in 1950 as Gala Performances of Ballet, co-founded by Alicia Markova and Dolin, its first artistic director (Krassovska was also a leading dancer, up to 1960). The Swan Lake sections in Never Let Me Go are based on what was then the British staging of the work (I’m assuming done by Dolin), the dancing very much in what was considered the ‘English’ dance style—focused on precision, clarity of line, and attention to choreographic detail.

By the 1950s, however, Russian companies, including the Bolshoi, had long changed their versions of Swan Lake, altering the style, mime, choreography—even the ending. It was also danced by Vaganova-trained dancers in an un-English-like style, integrating emotional expression with a strong yet fluid technique, and infused with feeling for the ballet’s overall meaning. Whatever MGM thought of as ‘Russian’ ballet at that time…that was not what it was presenting in its film. Not even close.

For comparison, here’s a clip from the 1960 film The Royal Ballet, released just a few years after Never Let Me Go, featuring the company’s prima ballerina, Margot Fonteyn, in Swan Lake’s second act, complete with Siegfried, Benno (remember him?), and swan maidens in long tutus—similar to the bits seen in Never Let Me Go (clip courtesy of the John Hall YouTube channel; scroll to the 4:35 mark to start):

Note how clear, crystalline, and correctly placed Fonteyn’s technique is; her body positions emphasize the purity and balance of her line, without the ‘fluttering bird’ flourishes seen today (Krassovska’s dancing was similar in style). In her arabesques she’ll stretch out like an arrow, as if to pierce the air, or even take flight; and her sudden, deep backbend from a pirouette in Siegfried’s arms hits our eyes like an exclamation point at the end of a sentence. Fonteyn’s emotional expression may seem subdued, yet that makes it all the more heartfelt; you sense here an Odette whose sorrow is a contained, private, inner wound. The choreography is equally clear and uncluttered, conveying what Antoinette Sibley in a 1981 Ballet Review interview said that Tamara Karsavina had told her—that Swan Lake at the Marinsky was once considered the purest of the classical ballets.

Now here’s the Bolshoi in 1953 (the year Never Let Me Go was released), from a film featuring the great Soviet-era ballerina Galina Ulanova—sans huntsmen and Benno; even the tutus are different (clip courtesy of the John Hall YouTube channel; scroll to the 3:50 mark):

Unlike Fonteyn, Ulanova doesn’t dart or pierce as she moves. Her dancing is more like a spiral; it melts, seamlessly, from step to step in an unbroken flow, continuously circling in on itself, the ballerina even luxuriating in the movement (she’s sensuous to watch); when she stretches in arabesque, it’s as if she wants to break out of her skin. Ulanova is almost pure emotion, dancing as if on one great breath; you sense in her performance that nothing exists beyond Odette’s sorrow, as head, neck, shoulders, arms, legs, and, especially, the back (nearly wrapping her torso around her partner’s body) are all used to express an all-encompassing surge of grief.

The choreography also differs for each company, some sections utterly unalike from each other, especially in the partnering. The British version emphasizes precise lines and patterns, the Russian one stresses big overhead lifts and impassioned emoting. Differences can be minor, such as the direction of the body (Fonteyn will face forward when Ulanova faces backward) or major, such as the motion across stage (Fonteyn travels back and forth or on the diagonal; Ulanova tends to stay circling in the center), and the position of the corps (Fonteyn flanked by lines of dancers, Ulanova surrounded by a curve). There are even slight differences in tempi (though the Russian film cuts some of the music and choreography, probably for length reasons), Ulanova adding more rubato, whereas Fonteyn stays on the music.

And then there’s the appearance of Benno.

Benno—do any SL stagings include him anymore, outside of the Trocks?—could be the square peg of Swan Lake, in that his character, as well as his choreography, no longer fits into the pas de deux as we know it today. He’s one of the ballet’s original characters; Cyril Beaumont in his book The Ballet Called Swan Lake notes Benno’s resemblance to Wilfrid in Giselle, in that he serves as the hero’s attendant and friend (but does any ballet-goer pay attention to Wilfrid?). Benno’s real claim to ballet fame was his appearance in the Ivanov-choreographed second act (or Act I, Scene II per Beaumont), during which Benno catches Odette several times as she swoons away from Siegfried to fall into Benno’s arms. It was his appearance, as the great dance critic Arlene Croce once noted, that made the Siegfried-Odette pas de deux “unlike any other in the world.”

For dance fans not versed in ballet history, though, Benno is, as the King of Siam would say, a puzzlement (a commenter on John Clifford’s YouTube channel regarding Fonteyn’s version wanted to know “who the person in green is”). A discussion on Benno and his necessity (or not) in Swan Lake’s second act is beyond the scope of this post. But what I do note, as mentioned earlier, is that Russian stagings, certainly by the mid-twentieth-century, had already, as Jack Anderson noted in his history The One and Only: The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, “dispensed with” Benno’s services (he may even have been cut soon after the 1890s performances). Benno, it seems, had been made redundant.

Croce defended Benno’s participation in the ballet, writing that his contribution served as “a poignant reminder of the Prince’s [Siegfried] youth.” And perhaps Benno’s presence does affect the overall performance, and interpretation, of the second act: Michael Somes’s British Siegfried is shyer, more hesitant as he encounters this exotic Swan-Woman creature (doesn’t the ballet’s original libretto indicate Odette can only be freed by a “virgin Prince”?; which may explain why Siegfried is so easily duped by Odile); whereas Konstantin Sergeyev’s Soviet Prince confidently offers help and succor. Benno’s non-presence might seem only a minor difference, but, as with the beat of a butterfly’s wings, who knows the long-term effect his deletion might have had on Swan Lake’s subsequent history and meaning?

What may be the most poignant aspect, however, of seeing Never Let Me Go today (over 70 years after its making) is that—dance audiences are no longer familiar with the Swan Lake performed in the film. I sense such a version, with its modesty, clarity, and stylistic precision, would look foreign to balletomane eyes today. The ballet’s style, aesthetic, performance, interpretation, characters, even tempi, have entirely changed—not just in the (non)appearance of Benno but in the elegance, restraint, and quiet musicality exemplified by such dancers as Krassovska and (especially) Fonteyn. That’s not to say today’s Swan Lake performances, and performers, are invalid or not up to par. It’s only that…something of the ballet’s history, tradition, its core, may have been lost to time, variety, and technical change; and that, as Croce notes, such “lost moments,” such as Odette’s opening pose on Benno’s arm, add a richness and complexity to the pas de deux—and to the ballet as a whole. It’s what, says Croce, makes Swan Lake “the most fascinating ballet in the world.” And maybe that’s what Mr. Gable, attending the ballet way back in Cold-War, pre-digital, pre-21st-century, we-still-have-Benno, days…thought so, too.

Bonus Clip: Courtesy of John Hall’s YouTube channel (an invaluable resource), here’s Nathalie Krassovska, circa 1950 (without interjected cuts and closer to the camera), dancing part of the the Sugarplum Fairy’s solo from The Nutcracker with the London Festival Ballet. Note her beautiful feet and legs, musicality, and precise lower body work: